Is OCD Something You Have, or Something You Do?

When working with new moms experiencing postpartum OCD and anxiety, one of the most powerful perspective shifts we can explore is the nature of OCD itself. Let’s explore the following question: is OCD something you “have,” a permanent condition that defines you or your brain? Or, is OCD something you do – a pattern of physical and mental behaviors that you can learn to recognize and reshape? Let’s dig in.

As a therapist specializing in postpartum mental health, I’ve observed that viewing OCD solely as something you “have” feels overwhelming and permanent, and reinforces the idea that it can’t be changed. It can create a sense of helplessness, shame, and additional fear – because you’re telling yourself that you’re at the mercy of a condition beyond your control. This is especially challenging for new mothers who are already navigating the profound transition into parenthood, when their sense of identity is already in question.

Let me be clear about something that might contradict what you’ve heard elsewhere: meeting the diagnostic criteria for OCD does not mean your brain is fundamentally or structurally flawed. Despite what the current medical and mental health paradigm often suggests, OCD is not necessarily a lifelong sentence. This narrative, though widespread, can be incredibly damaging. It can make people feel hopeless about their recovery before they’ve even begun.

Think about it: if you truly believed that your brain was permanently broken, how motivated would you be to work on recovery? The belief in your ability to overcome OCD isn’t just positive thinking—it’s a crucial component of the healing process. When we internalize the message that we’re permanently “disordered,” we not only unconsciously limit our potential for growth and change, but we also reinforce the types of beliefs that maintain OCD (i.e. the belief that we shouldn’t ever experience disturbing thoughts and imagery and that we are bad or flawed people if we do).

Let that sink in.

The Real Culprit: Response, Not Thoughts

Here’s a crucial truth that often surprises my clients: it’s not the presence of unwanted thoughts or images that creates or indicates a disorder. Intrusive thoughts are a universal human experience— a normal aspect of consciousness that on some level we all navigate – and they are particularly common among new parents. What transforms these normal experiences into a “disorder” is our response to them. When we treat these thoughts as meaningful threats that require immediate action, when we fight against them or try to control them, when we tell ourselves that these thoughts aren’t allowed, that they aren’t acceptable to experience – we inadvertently invite disorder into our lives. We exhaust ourselves trying to eliminate these unwanted thoughts, until the fight against them consumes more of our life than the thoughts themselves ever did. Our world shrinks as we focus on making anxiety disappear, leaving little room for the things and people we value most.

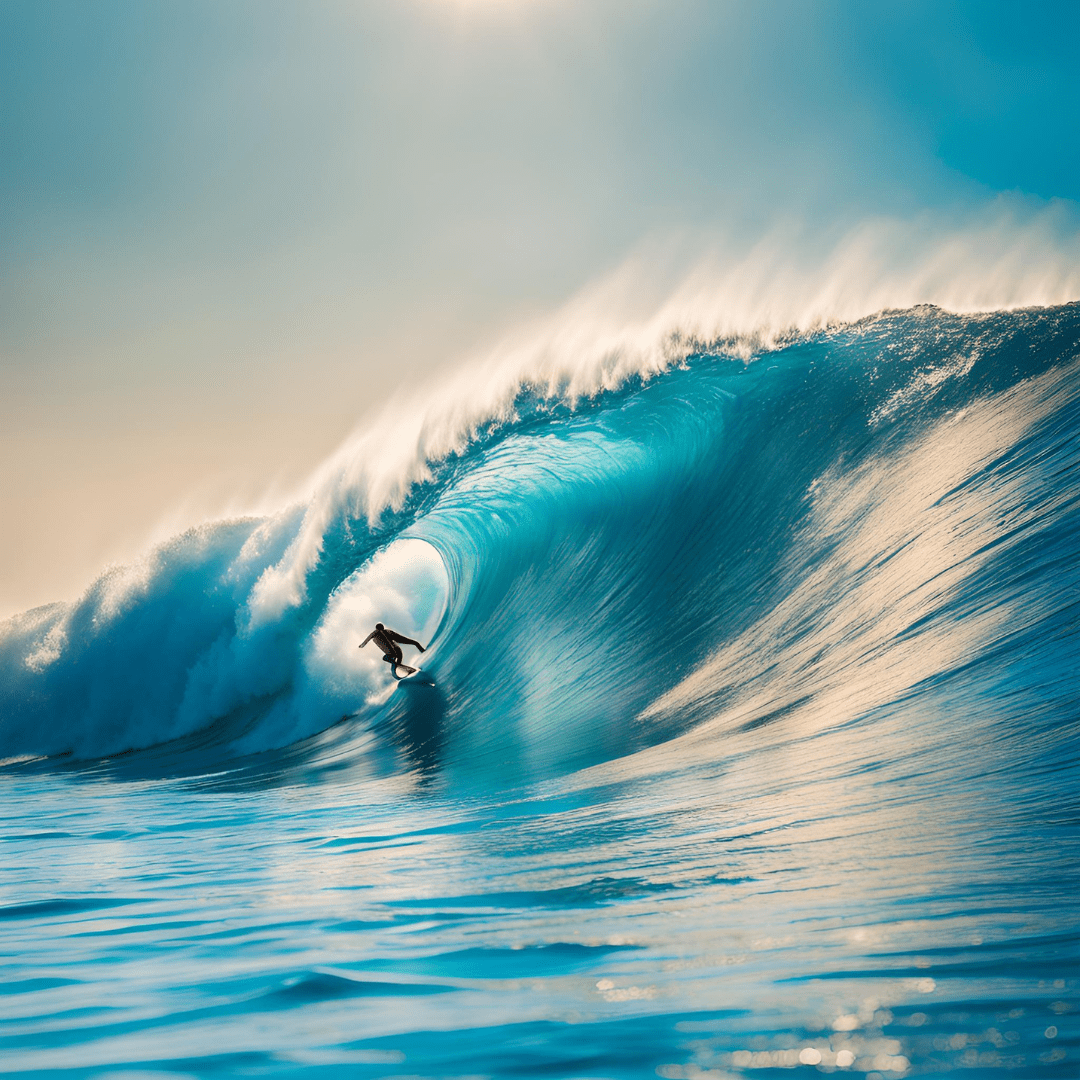

Think of it this way: intrusive thoughts are like waves while you’re in the ocean. Everyone experiences them. The difference lies in how we respond when these waves appear. Do you exhaust yourself trying to stop or control the waves? Are you panicked, trying to flee the beach entirely? Or, do you learn to surf—moving with the waves rather than against them, learning to staying upright even as they pass beneath us, inevitably getting knocked down, but getting back up again and again? It’s not the waves themselves that determine our experience, but how we’ve learned to respond to them.

The OCD & Anxiety Cycle

When we break it down, OCD manifests as a series of mental events and emotionally driven reactions. Let’s take a look at the cycle:

- You’re feeling fear and anxiety

- You experience an intrusive thought (which, importantly, all new parents do at some point)

- You experience a surge of fear in your body

- You engage in mental and/or physical safety behaviors to try to reduce the anxiety and feelings of uncertainty, such as seeking reassurance and avoiding certain triggers, and analyzing/replaying thoughts in your mind

- You feel a sense of temporary relief, a temporary glimmer of certainty….

- and then the mind tosses up more intrusive thoughts, and the cycle continues because you’re engaging in behaviors that reinforce the thoughts.

These are all things you DO, not things you ARE. This distinction is crucial because actions can be adjusted, patterns can be reshaped, and responses can be rewired. The science is clear: our brains are constantly changing and adapting, forming new connections and pathways in response to our experiences.

For the new mom who can’t stop checking if her baby is breathing, or who has disturbing intrusive thoughts about harm coming to her child, this perspective can be transformative. Rather than seeing herself as “broken” or “damaged,” she can begin to recognize these patterns as learned responses to anxiety—responses that can be understood and gradually modified.

Think of it like learning to drive. Initially, you might grip the steering wheel too tightly and choose to drive without listening to music. These are things your mind is telling you to DO as an attempt to lessen the feelings of anxiety and inexperience – these are not fixed personal traits. With practice and guidance, you develop new patterns and responses. The same principle applies to OCD and anxiety recovery.

This doesn’t minimize the very real challenges of OCD. The distress, the intrusive thoughts, and the compelling urge to engage in safety behaviors are intense and valid experiences. But viewing OCD as a set of behaviors, rather than an immutable condition, opens up possibilities for change – and a very real opportunity for growth.

From Burden to Blueprint: Transforming How We View OCD

For new mothers, this perspective can be particularly empowering. Motherhood already brings enough labels and judgments—adding “OCD sufferer” to that list can feel like another heavy burden to carry. But understanding that OCD involves patterns you can identify, work with, and eventually break rather than a permanent state of being, creates space for growth and healing.

In my practice, I’ve witnessed how this shift in perspective helps mothers:

- Separate their identity from their symptoms

- Recognize their agency in changing their relationship to thoughts and emotions

- Develop more self-compassion during the recovery process

- Engage more actively in their lives and take charge over their mental health

Remember: You are not your mind. You are not the safety behaviors in which you’ve been engaging. With support and practice, you can learn to do things differently. Your worth as a mother and as a person is absolutely not defined by these patterns.

The key to healing lies not in eliminating unwanted thoughts—an impossible and counterproductive goal—but in changing how we respond to them. When we learn to hold these thoughts more lightly, to let them exist without wrestling with them, we begin to reclaim our freedom from anxiety’s grip.

Freedom Begins By Questioning What You Believe

If you’re struggling with postpartum OCD and anxiety, know that seeking help isn’t about treating some inherent flaw or managing a permanent condition—it’s about confronting and releasing the false beliefs that have been holding you captive. These might be beliefs about what makes you a good mother, about which thoughts and feelings are acceptable to have, about what experiencing anxiety means about you as a person, or about your capacity to experience difficult emotions without breaking. Recovery happens when we begin to question these beliefs and allow ourselves to experience the full spectrum of human thoughts and emotions without judgment or resistance. Your journey isn’t about becoming a different person—it’s about freeing yourself from the constraints of beliefs that were never true to begin with, and stepping into a more authentic relationship with your experience of motherhood.

Disclaimer: While these strategies can be helpful, they are not a substitute for professional mental health support.

© 2025

leave a comment

Ready to take the next step?

Schedule consult call with me here